History of FTU & UCF

In the early 1960s, Orange County’s future seemed tied more and more to the aerospace industry. The Mercury program from nearby Cape Canaveral captivated the nation and the new Martin Marietta facility in South Orange County was creating a new generation of rockets and missiles. There was an increasing demand for local educational facilities where the growing numbers of scientific and technical employees at these and other electronics and engineering companies could pursue advanced studies.

Business, professional and government leaders quickly enlisted in the cause of building what some called a “Space University” to educate current and future students for promising space-age careers in engineering, electronics and other technological professions needed to sustain the growth of these industries in Central Florida. William H. Dial, a bank president and lawyer with friends in Tallahassee, began lobbying for passage of what became Florida Senate Bill No. 125. He enlisted the aid of former state Senate President William Shands, who used his many connections in the Florida Senate to help convince lawmakers to support the bill. With Shands’ help, and the editorial support of Orlando Sentinel publisher Martin Anderson and Senator Beth Johnson of Orange County, the bill finally moved out of committee and easily passed both the House and Senate. A citizen’s advisory committee, led by Dial, was formed to help finance and build public support for the university.

On January 24, 1964, seven months after the governor had signed Bill No. 125 into law, the Board of Control (from 1905 to 1965, then the Board of Regents, or BOR, from 1965 to 2001 and now the Board of Governors) selected a 1,227-acre tract along Alafaya Trail in northeast Orange County, 12 miles northeast of downtown Orlando. It was selected as being the most accessible to the largest number of people in the east central Florida area. Most of the land was acquired from Frank Adamucci, a New Jersey building contractor who donated 500 acres and sold another 500 acres for $500,000. Donations from other landowners gave the university more frontage on Alafaya Trail and pushed the total size of the parcel to 1,227 acres.

In order to be eligible for funding from the 1965 Florida Legislature, the site had to be available immediately. It had been expected that Orange County would buy the property and donate it to the state, but the County lacked the necessary funds. Eighty-nine Orange County residents pledged a total of $1 million in cash and securities to secure the purchase of the site. Millions more would be needed to begin construction. Martin Anderson called Governor Haydon Burns and Dial flew to Tallahassee to argue for immediate funding. The Governor agreed and ordered the project to be moved to No. 1 on the higher-education funding priority list.

The next step in the university’s formation was the selection of a president. In October of 1965, the BOR unanimously chose Charles N. Millican, dean of the College of Business Administration at the new University of South Florida in Tampa. A few months later, in December, Millican opened the University’s first offices above a drugstore at Church Street and Orange Avenue in downtown Orlando. Among his first tasks were making decisions on designs and drawings for the buildings, recruiting academic and administrative staff members, planning curriculum and giving speeches.

By the time Millican was chosen as president, the BOR had already determined that Central Florida’s higher education needs had changed from what legislators had originally envisioned. Market surveys of high school and community college students taken showed that Central Florida needed business people and teachers in addition to scientists and engineers. So, the regents decided to include liberal arts, education and business studies in the university curriculum, in addition to computer and engineering courses.

In February 1966, the Citizens Advisory Committee and the Board of Regents, hoping to attract more high-tech industries to the area, selected the name Florida Technological University (FTU) for the new school. The name had the advantage of being both descriptive and distinctive, easily remembered and shortened, and not geographically restrictive.

Governor Claude Kirk presided over the FTU groundbreaking on March 19, 1967. Eighteen months later on October 7, 1968, classes began with 1,948 students, 90 instructors and 150 staff members. Fifty-five degree programs were offered within five colleges: Business Administration; Education; Humanities and Social Sciences; Natural Sciences; and Engineering and Technology. The first two of the University’s nine regional campuses, Daytona and Cocoa, also opened that year.

Previously to the school opening, on April 5, 1968, the official university seal, Pegasus, the winged horse of the muses in Greek mythology was selected, with a single star and the motto “Reach for the Stars” and the school colors of Black and Gold were introduced. The motto was a challenge and admonition to students to always aim high, try harder and go beyond what they believed possible. Pegasus contrasted and connected the old and new, the humanities with science and technology. In 1974, at the request of students, a competition was held to create the FTU alma mater, with music faculty member Dr. Burt Szabo’s music and lyrics selected from the many entries.

In 1978, Dr. Millican decided to return to teaching in the College of Business, and Dr. Trevor Colbourn became the university’s second president. The new president realized that the community population had changed and diversified, and so had the University. Many students were now enrolled in widely varied academic programs, reflecting a shift in demand for strictly technological and scientific education as the local economy diversified. In December 1978, Governor Reuben Askew signed legislation changing the school’s name from Florida Technological University to the University of Central Florida. By the time Dr. Colbourn resigned to return to teaching history in 1989, UCF had a football team, a marching band, four doctoral programs, a Research Park, and seven endowed Chairs. The academic programs had also been diversified and reorganized to create the College of Arts and Sciences.

Dr. Steven Altman became the University’s third president. His contributions ranged from hiring strong deans to raising research dollars to making clear growth plans to boost the University’s profile. By Spring of 1991 the University had completed a “blueprint” for UCF’s future that included a Master Plan for new construction to accommodate a growing research mission and a student body that was expected to more than double in the next twenty years. UCF was now a “Metropolitan University” that would provide facilities and academic programs to match the community’s greatest needs.

When Dr. John Hitt arrived from the University of Maine in 1992 to become the University’s fourth president, one of his first moves was to draw five clear goals for the schools that would become part of the strategic plan and take the University into the 21st Century. As of March 2011, 56,235 students are enrolled, making UCF the second largest school in the country. UCF has 212 degree programs in 12 colleges and 9 regional campuses. Among UCF’s alumni and students are a Miss America, a Pulitzer Prize winner, a NFL quarterback, a Rhodes scholar, a NASA astronaut, a World Cup/Olympic Soccer champion and the five creators of “The Blair Witch Project”; the most successful independent film of all time.

UCF has become one of the nations leading metropolitan research universities through its community and corporate partnerships. UCF still stands for “Under Construction Forever”; planning, building and creating new programs, facilities and opportunities for Central Floridians as it continues to “Reach for the Stars.”

Information compiled by Becky Hammond, Senior Library Technical Assistant, Special Collections & University Archives, UCF Library, from the following sources:

- Accent, University Archives, UCF Library Call # LD 1772 .F9 A1125

- The Central Florida Future, University Archives, UCF Library Call # LD 1772 .F9 A1438

- Department of UCF News and Information https://www.ucf.edu/news/

- Emphasis, University Archives, UCF Library Call # LD 1772 .F9120 E47

- FTU Scrapbook, University Archives, UCF Library Call # LD 1772 .F9 A6829

- Pegasus, University Archives, UCF Library Call # LH 1 .U55 F778

- Orlando Sentinel Newsbank

- Sheinkopf, Kenneth. Accent on the Individual: the First Twelve Years of Florida Technological University, University Archives, UCF Library Call # LD 1772 .F892 S47 (read full text)

- UCF Alumni Association https://ucfalumni.com/

- UCF Office of Institutional Research https://ikm.ucf.edu/

- The UCF Report, University Archives, UCF Library Call # LD 1772 .F91 A18325

Black Student Union History

The following research was conducted by Brandon Nightingale in 2018 and is used with his permission. Images are courtesy of UCF Special Collections & University Archives.

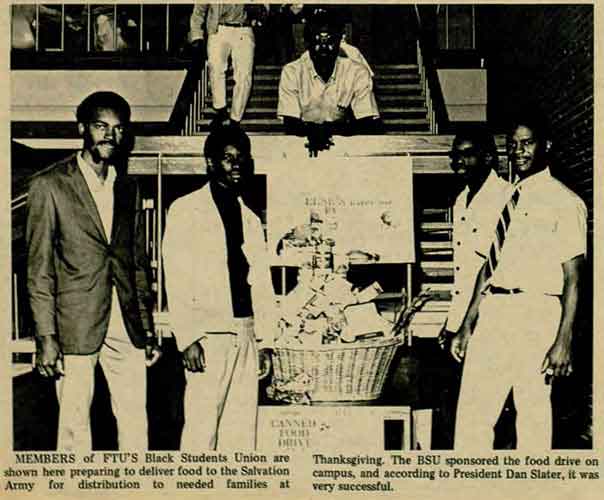

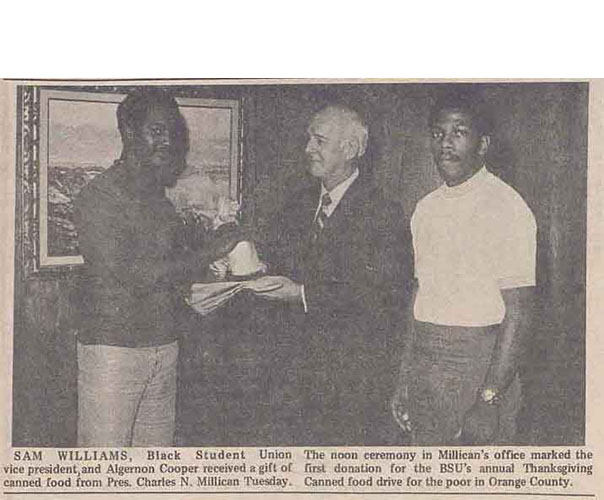

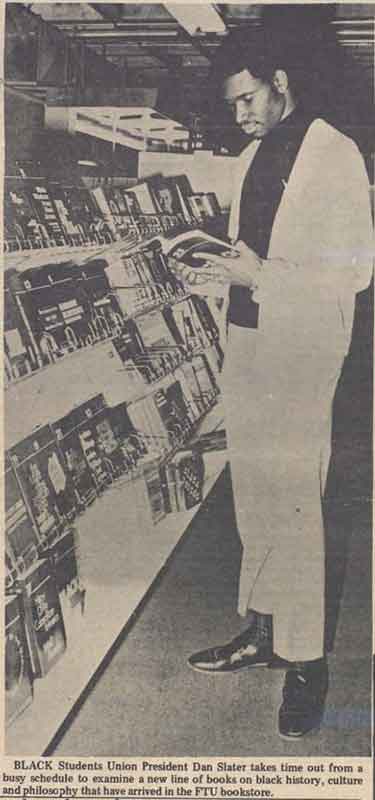

On October 29, 1969 the Black Student Union was formed at Florida Technological University (now University of central Florida). Because most of the students at FTU were white, black students felt the need join together to create real change on campus. Student leadership positions, clubs, fraternity and sorority life were all held by white students during this time. Sixteen out of the twenty-five black students at FTU collectively formed a union that would fill the absence of black leadership on the campus for many years to come. Dan Slater and Roland Williams were elected as the first President and first Vice President of the BSU in 1969. In an interview with the Central Florida Future Slater stated that the BSU would provide “an organization that black students can identify with to the fullest” The union wanted to stress black pride and unity, help to improve communication with administration, and begin to celebrate the lives of well-known black Americans. The only requirement to join was that you needed to be a FTU student and that all officers must obtain a minimum 2.0 GPA. Within the first year of existence, the BSU started their first community service project. The Thanksgiving Food Drive would become an annual event where the BSU collects and delivers food to the Salvation Army to be distributed to less fortunate families within the Orlando area. 1, 2, 3

Under the leadership of Dan Slater, the Black Student Union began to demand change on campus. In December of 1969, Slater and five other representatives of the BSU met with President Charles Millican to address their concerns over the lack of black faculty and black history curriculum on campus. After some discussion, the six students walked out of the meeting because they felt as if their voices weren’t being heard and nothing would be accomplished. Finally, in the spring of 1970, President Millican gave in and History 324-01, Black American History was added to the course schedule. The course would focus on the “history of the Negro in Africa and the United States.” Joseph Taylor, an assistant professor of American History at Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach would be asked to teach the course, making him the “first part-time black faculty member at FTU.” The black history course was supposed to be the start of the black studies curriculum that the students demanded during the meeting with President Millican. 4, 5

From the Central Florida Future, Vol. 02 No. 18, 2/27/1970

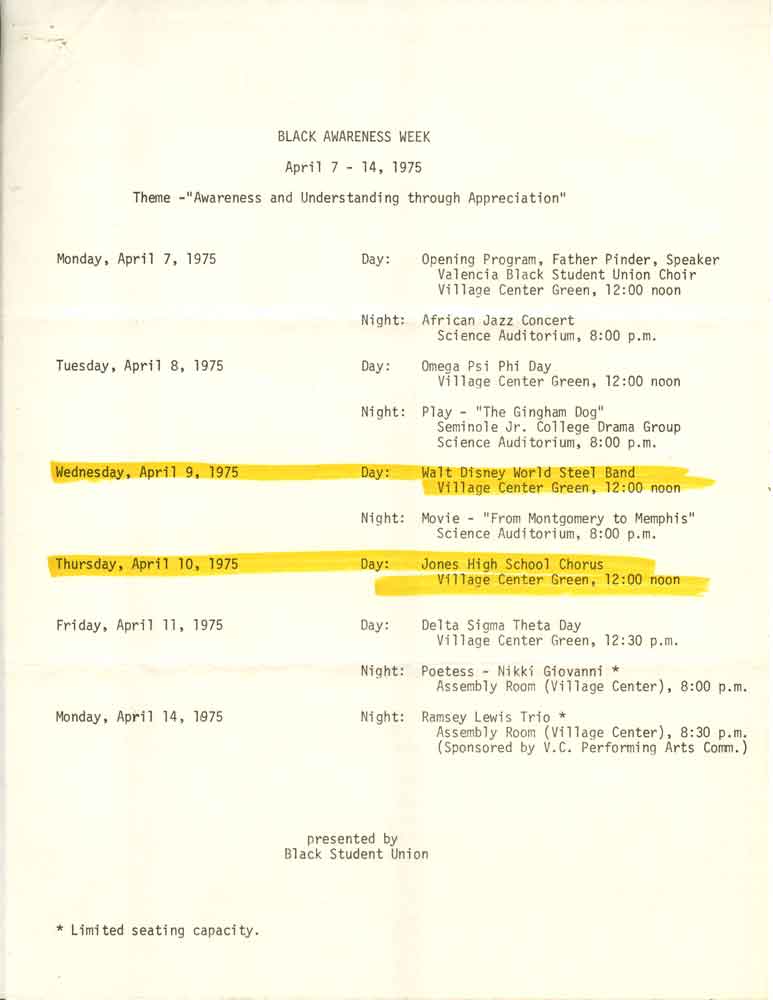

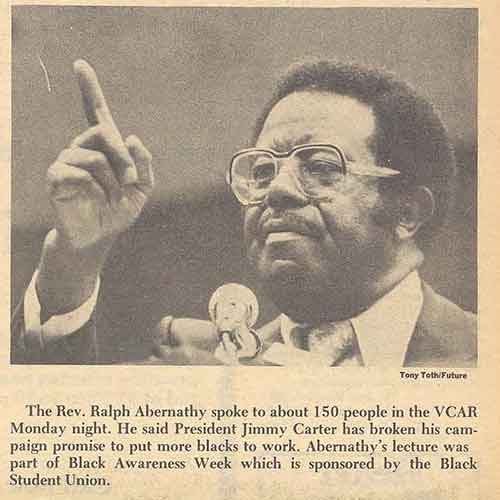

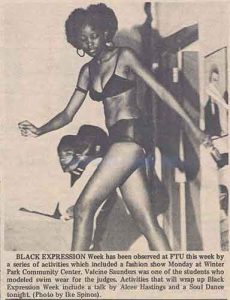

By 1970, the BSU went on to establish an annual Black Liberation Week, during the month of February, honoring the legacy of Malcolm X, assassinated on February 21, 1965, by playing old videos and speeches of his on the campus. In the spring of 1972, the BSU started Black Expression Week. In 1975 the name was changed to Black Awareness Week. This was seen as an “opportunity for black FTU students to celebrate African and Afro-American culture.” The week included a fashion show, tours given to local area high school students, a concert, a day for students to dress in African clothing, and words from a guest speaker. 6, 7

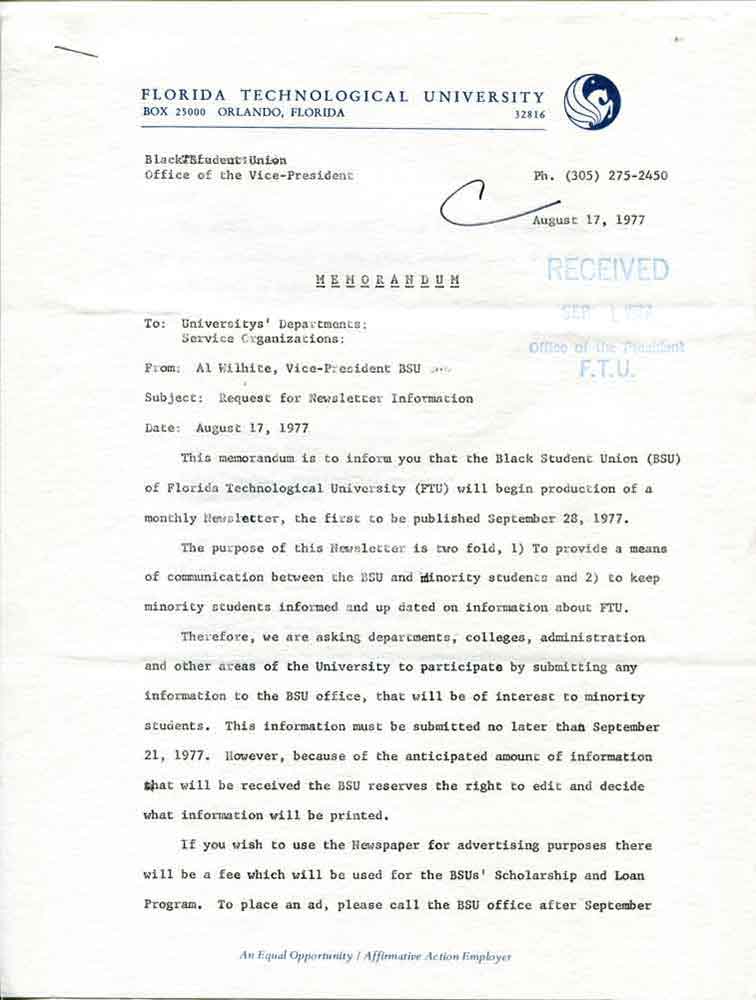

The BSU at FTU stayed in communication with the other Black Student Unions across the state of Florida. In 1977, under the leadership of President John Stover, they formed the Inter-Campus Committee with the Black Student Union at Rollins College in nearby Winter Park, Florida. The committee would consist of members from both colleges, making the relationship between both unions stronger than ever. The BSU also had plans to connect with the black students at Valencia and Seminole Community Colleges. To “provide a means of communication between the BSU and minority students at FTU,” on September 28, 1977, the BSU began publication of a monthly newsletter titled “Our Commitment… The Betterment of Life.” Although the publication only lasted a few years, the BSU began to expand its network to wide range of students across the region. 8, 9, 10

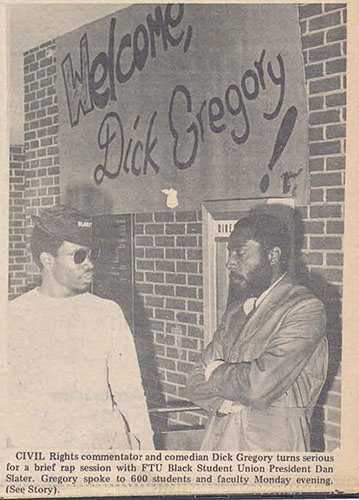

In the late 1970s, the Black Student Union began to face hard times. During the fall of 1977, they were forced to cancel all events due to the lack of funding from the Student Government. In a meeting with two members of the BSU and 3 members of administration on campus, the BSU threatened to stage a “sit-in” during the FTU Open House on November 6 if administration didn’t approve their list of 20 demands. The demands included getting funding from the Student Government and establishing a black studies program on campus. The BSU had been an active organization on campus that provided services for all students on campus. Despite not having much money, over the years the BSU brought civil rights leaders to campus and created events for students on campus to attend.

Finally, the administration listened and in 1978, the same year FTU became the University of Central Florida, the BSU was placed under the branch of funding by the UCF Student Government. Although the BSU began to gain recognition on the campus, they were still a black organization on a predominantly white campus. Because of this, they began to face times of difficulty as the years went by. In April of 1978, the Black Student Union was accused, by the Student Government President Bob White, of charging money for its annual Spring Fashion Show. The show was already being funded by the Student Government, and the BSU would be in direct violation of organizational policy of clubs on campus if these accusations were found to be true. This would lead to an audit of the Black Student Union’s accounts ordered by Bob White which was made public via the Central Florida Future. This would lead to a war of words between President Stover and President White, and even students chimed in on the Editorial Board within the publication. Although the BSU was cleared of any wrong doing, the damage had already been done. Because the BSU was being audited, their accounts were placed on hold and this prevented them from conducting their legislative elections. 11, 12 The feud between the BSU and Student Government began to intensify, as the days went by. Student Government President Mark Omara, who inherited the dispute from previous president Bob White, attempted to diminish the BSU. He began to campaign for “a minority student organization on campus to serve all the minority students.” Omara often attacked BSU, blaming their lack of success on leadership within the organization. 13, 14, 15, 16

Finally by 1979, new faces were in office, time passed and the feud had come to an end. 17 The BSU could finally look towards the future and achieve new heights. The organization went on to establish UCF’s first Gospel and Cultural Choir, originally the Black Student Choir, in 1979. Students that were members of the BSU became motivated to get involved in other organizations on campus. In 1980, James Blount, former VP of the BSU, went on to become UCF’s first black Student Government President and in 1981 he became the first UCF student to be appointed to Florida’s Board of Regents by the governor. 18, 19, 20

Under the leadership of Richard Sherrod in the late 80s, the BSU reached its greatest success. Sherrod took over as interim president in the summer of 1988 and became President in the fall. Sherrod wanted to “increase student participation, become more visible in the community, and provide programs and functions for the general student population.” Under Sherrod’s reign, the BSU was able to earn more money from the Student Government, under Sherrod’s reign, than ever before. This was only the first of new changes to come for the union. Membership had reached 250 members, something that had only been done once back in 1977. In the fall of 1988, the Black Student Union would change its name to the African American Student Union. The change came about at a state conference on March 3-5, held in Miami. Representatives from BSUs all over the state of Florida gathered to discuss the name change. Following a two year movement to get the name changed by representatives across the state, it became official. The reasoning behind the change was that many felt that the term black “is a concept which does not give a reference to any country and it has negative connotations.” 21, 22

The Union had finally gained credibility across campus and things were finally going well. The BSU was doing so well that in April of 1990, there became a push for a “white union” to form on campus. This was an attempt to undermine the work of the BSU, even though the BSU didn’t discriminate and had white members within the organization. While the news of the “white union” did make headline in the Central Florida Future, no union was ever officially formed on campus. 23

The African American Student Union eventually changed its name back to the Black Student Union. Today, the BSU is still an active organization and continues to provide a platform for minority students on campus. Members consistently take part in social justice programs and community service projects throughout the Orlando community. Together, BSU strives to create a ‘home away from home’ environment for all members, and to encourage students to become campus leaders. 24

References

- (1982). BSU Celebrates 14th Anniversary. Central Florida Future, 15(10), 29.

- Smith, N. (1969). Blacks Form FTU Group. Central Florida Future, 2(5), 8.

- (1969). Black Student to Aid Needy. Central Florida Future, 2(7), 4.

- (1969). Black Studies Accepted Despite Walkout by BSU. Central Florida Future 2(10), 1.

- (1970). Minority Groups Are Represented. Central Florida Future, 2(21), 2.

- (1970). Black Liberation Week: Tribute to Malcolm X. Central Florida Future, 2(18), 1.

- (1972). Black Student Union Salutes Afro-America. Central Florida Future, 4(22), 3.

- (1977). BSU Forms New Committee to Plan Cultural Programs. Central Florida Future, 9(20), 9.

- (1977). BSU Provides Services: Stover. Central Florida Future, 10(7), 7.

- University of Central Florida Office of the President: H. Trevor Colbourn Presidential Papers 1948-2006, (Box 3, Folder: Afro-American Studies, 1969). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL.

- Holfe, R. (1977) Administration Okays BSU’s proposals. Central Florida Future, 10(11), 1.

- Kilsheimer, J. (1978). Black Student Union Finances to be audited by SG Accountant. Central Florida Future, 10(29), 1,6.

- Kilsheimer, J. (1978). Audit Clears BSU of Violations. Central Florida Future, 10(33), 1.

- Barry, A. (1978). A&SF Supplement Up in the Air. Central Florida Future, 11(3), 1.

- Gugel, D. (1978). Omara Suggests formation of Minority Student Group. Central Florida Future, 11(9), 1.

- Omara, M. (1978). Concern over BSU with ‘Legitimacy’ of Leaders. Central Florida Future, 11(10), 8.

- Cheves, V. (1979). BSU Resolves Problem of Communication with SG. Central Florida Future, 12(9), 1.

- (1979). Black Students to Organize Choir. Central Florida Future, 12(2), 4.

- Gugel, D. (1980). Blount, Marchena Win Election. Central Florida Future, 12(29), 1.

- Hawley, K. (1981). Governor Appoints UCF Student to BOR. Central Florida Future, 14(4), 8.

- Lee, M. (1989). AASU Selects Sherrod to Continue Positive Influence. Central Florida Future, 22(10), 1.

- Green, V. (1989). BSU Becomes AASU at Convention. Central Florida Future, 22(10), 1.

- Stoker, M. (1990). UCF White Union May Form. Central Florida Future, 22(60), 1.

- http://www.ucfbsu.org/

University Documents

Below is a selected list of online university documents for research.

Wish to add your university document to this page? Please email our department.

- State University System of Florida Board of Governors

https://www.flbog.edu/ - University of Central Florida Board of Trustees

http://bot.ucf.edu/ - University of Central Florida President

http://president.ucf.edu/ - University of Central Florida Provost

http://provost.ucf.edu/ - UCF Strategic Plan

https://www.ucf.edu/strategic-plan/ - News and Information

https://www.ucf.edu/news/ - Office of Institutional Knowledge Management (Facts about UCF)

http://ikm.ucf.edu/ - University Marketing

https://www.ucf.edu/brand/ - UCF Connect (Regional Campuses)

https://connect.ucf.edu/ - Faculty Senate

http://www.facultysenate.ucf.edu/ - Undergraduate Catalog, current

https://www.ucf.edu/catalog/ - Undergraduate Catalog, previous

http://stars.library.ucf.edu/ucfcatalogs/ - Graduate Catalog, current

https://www.ucf.edu/catalog/ - Graduate Catalog, previous

- http://stars.library.ucf.edu/ucfcatalogs/

- Student Handbook: The Golden Rule

http://www.goldenrule.sdes.ucf.edu/ - Student Government

https://studentgovernment.ucf.edu/ - UCF Alumni

http://www.ucf.edu/alumni-giving/ - Athletics

https://ucfknights.com/ - Facilities Planning

https://fp.ucf.edu/ - Library Annual Report

https://stars.library.ucf.edu/lib-annualreports/ - Master Plan

https://fp.ucf.edu/mp2015 - UCF Statistics & History Research Guide

http://guides.ucf.edu/statistics-ucf - Dissertations and Theses Research Guide

https://guides.ucf.edu/thesesanddissertations